[ad_1]

From the Summer 2022 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Where does evolution happen the fastest? What affects the likelihood of a species becoming extinct? AVONET, a new database containing detailed measurements of nearly every bird species in the world, opens the door for scientists to study complex questions like these by revealing global ecological patterns and bird evolution.

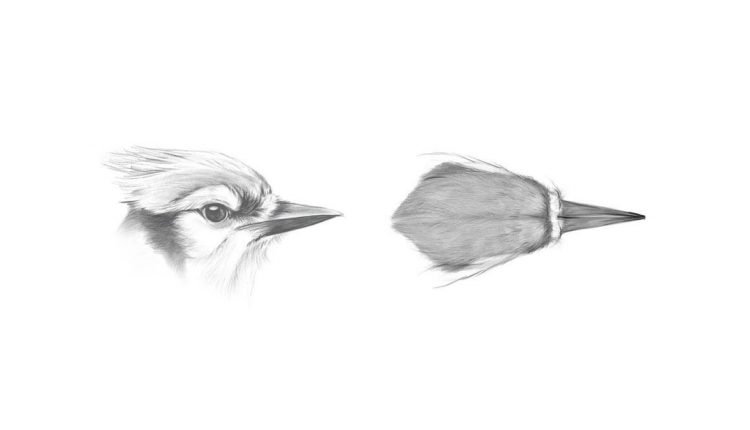

A special issue of the journal Ecology Letterspublished in February 2022, introduced it new open-source database of morphological, ecological, and geographical data for nearly 11,000 bird species, including detailed beak, wing, tail, and tarsus (lower leg) measurements—what the authors call functional traits.

According to Joseph Tobias, a biology professor at Imperial College London who led a decade-long effort to assemble the massive new database, the size and shape of beaks, wings, tails, and legs provide a wealth of information about how species fit into the local diet. web, how they move, and how far they travel.

Tobias says the idea for AVONET began in the late 1990s and early 2000s, while he was venturing on field expeditions in Paraguay, Ecuador, and Indonesia. There he measured birds and collected similar datasets of functional traits at smaller scales.

“Measuring many tropical forest species, it became clear that there were some patterns. … You can look at a bird’s legs and know how much time it spends on the ground. You can look at a bill and know something about what it eats. Wing shape can tell you how long a bird flies,” Tobias said. “I wondered if some of these patterns were global, and how that might be useful for research.”

These functional traits have played a role in the study of birds since Darwin’s time. In a classic example, differences in bill size and shape among a group of closely related birds in the Galapagos, known as Darwin’s finches, have led to insights about natural selection and the evolutionary relationship between beaks. of the bird and what it eats.

Tobias said that over the past few decades ecologists and evolutionary biologists have increasingly looked to functional traits to help answer big questions about diversity and evolution. But the scope of this type of research is limited to specific regions or groups of birds, because there is no database of measurements for all birds in the world.

The AVONET project really gained steam in 2012, Tobias said. That’s when Catherine Sheard, a PhD student in his lab at the University of Oxford at the time, began a project to assemble trait data for all of the world’s 6,000-plus passerines—more than half of all species of birds.

Sheard spent more than two years visiting museums on both sides of the Atlantic, including the American and British Museums of Natural History, personally measuring about 11,000 specimens—a process he says was both exhilarating and terrifying. .

“I measure specimens collected in the mid-1800s by Darwin and Wallace, also type specimens of extinct species,” Sheard said. “It is an honor, and very stressful to handle these fragile and irreplaceable birds.”

From there, Tobias and his team worked on the remaining 4,000-plus species, eventually enlisting the help of more than 100 collaborators (including Cornell Lab of Ornithology researchers Natalia Garcia and Eliot Miller, who measured specimens at the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates). All told, the AVONET data contain measurements of more than 90,000 specimens for approximately 11,000 species.

Benjamin Freeman, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of British Columbia, is a scientist who contributed measurements to the project, and he has published research using AVONET data. In a study appearing in the same special issue of Ecology LettersFreeman used charge size data from 1,000 closely related pairs of birds around the world to show that evolution appears to occur more rapidly in temperate zones than in the tropics—a result that contradicts some existing theories.

“Previous studies looking at this may have used 100 or more species pairs,” Freeman said. “We used over 1,000 pairs from all different parts of the world. … That is key to being able to tell this pattern [of faster evolution in higher latitudes] happening all over the world.”

AVONET also inspired Brian Weeks, an evolutionary ecologist at the University of Michigan, to test a theory about extinction risk. According to Weeks, studies have shown that certain traits such as larger size, specialized diets, and poor dispersal ability can increase the likelihood of species becoming extinct. By combining AVONET data with another global database, the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Weeks was able to show that birds in diverse ecological communities face a lower risk of extinction than birds in simpler ones. ecosystems, regardless of the physical characteristics that may cause them. extinction-prone. In other words, biodiversity in an ecosystem can protect birds with traits such as large body size or stubby wings that may be at risk of fledging. Weeks says results like these can help shift the conversation when it comes to conservation science.

“We think of diversity as the endgame of conservation, but this shows that it’s important to recognize that diversity itself has benefits to species,” Weeks said. “Another call to move away from the species as the unit of conservation, and towards the ecological community [as a whole].”

According to Joseph Tobias, the work on AVONET is far from over.

“Right now we have an average of nine to 10 specimens measured per species, which allows us to look at the relationships between species,” Tobias said. “If we get to 100 [specimens] for each species, we can also start looking at variation within species, which opens up a whole new layer of research possibilities.

To that end, Tobias hopes that anyone, anywhere in the world, who measures birds—whether in museums or out of mist nets—will consider using the AVONET protocol and contribute data to the project .

“AVONET is about making it easier to get information at scale, and I’m really excited about the new ideas that are emerging,” Tobias said. “I think this data can be used in ways we can’t even imagine.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.