[ad_1]

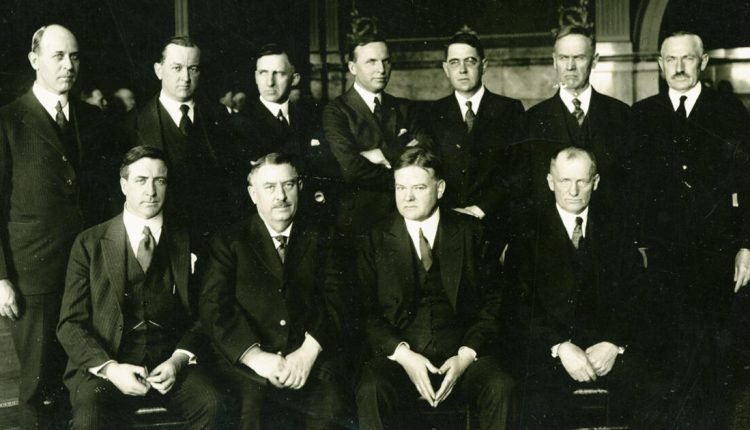

On November 24, 1922, representatives of the seven states of the Colorado River basin—Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming—gathered in Santa Fe, NM, to sign the Colorado River Compact, which was adopted as law a regime. for dividing river water. Without exception, these men were newcomers to a region inhabited since ancient times by Native American Tribes. Two of them represented states that were only a decade old, none represented states that were more than 75-years old, and their purpose was to enable colonial settlers to establish a foothold through irrigation. -driven economic development.

On the centennial anniversary of the creation of that important document, as Colorado River reservoir levels fall to historic lows, Native American Tribes remain denied access to the water they deserve, and we see the destruction of freshwaters -dependent ecosystems throughout the basin, it seems worth asking whether the Compact is serving us well.

Today, the elected leaders of these seven states still regard the Compact as an important, foundational document, and despite its flaws, it is still considered the foundation of the “Law of the River” which also includes International Treaties with Mexico, federal and state laws. , and regulations.

They point to the main purpose of the Compact: “to provide for the equitable sharing and apportionment of the use of the waters of the Colorado River System.” By 1922, “prior appropriation” was established as the law of the land within each of the Colorado River Basin States, meaning that those who first drew water from the river would have senior water rights and the development of water that follows will be subjected. If there is not enough water to fulfill all rights, the senior right gets water and the junior right gets none. Negotiators from the “Upper Basin” states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming shared the concern that water users in the “Lower Basin” states would have California and Arizona use Colorado River water before they could use (the Lower Basin was also in Nevada, but there were so few people living there in 1922 that they were not seen as a threat). The evidence: in 1901, irrigators began diverting vast amounts of Colorado River water to farms in California’s Imperial Valley and Arizona’s Yuma Valley. The Upper Basin states do not put anywhere near those quantities of water to use and seek the right to develop at their own pace in the future, without having to worry that the Lower Basin states will claim the entire supply of the Colorado River to superior rights. The Compact’s solution is to divide Colorado’s water equally between the Upper and Lower Basins, regardless of the rate at which the water is generated.

It is the “equal division” of Colorado’s water that many continue to view as important. A century later, “equitable apportionment” between basins still makes sense, but if the seven Colorado River Basin States want to keep the Colorado River Compact in place, they have a lot of work to do, as it is indisputable that in 2022 Colorado River management is broken. The most visible problem lies in the historically low-lying reservoirs and very high risk of crisis-level water shortages for 40 million people, and 5.5 million hectares of agricultural land dependent on the river—but that’s not the its extent. The Compact ignores—or deliberately avoids—values that we must uphold today as important, including justice for tribal communities and sustainable ecosystem management. States today may view the Compact as essential to maintaining peace, but if they want the Compact to survive, they will need to quickly adapt the Compact to today’s standards by adopting rules and agreements that solve many problems:

The Compact will not achieve what the states define as an equitable division of river flows today. An extended drought exacerbated by climate change has led to an average Colorado River yield of 12.4 million acre-feet of water in recent decades, while the Compact is based on a flow of at least 16 million acre-feet . The Compact specifies how to achieve equitable distribution of water between the Upper and Lower Basins by prohibiting the Upper Basin from depleting flows to the Lower Basin below an average of 75 million acre-feet in any 10 years, but there is not enough water for the Upper Basin to meet that obligation and generate another 7.5 million acre-feet of water for annual use. Moreover, as climate change increases aridification in the basin and average water yield further declines, the Upper Basin’s access to the Colorado River continues to diminish. In short, drought and climate change have thrown a wrench into the Compact’s framework for basin management. Moving forward, states need to find a way to translate the realities of climate change into a governance framework or risk the effects of an uncertain future for communities, economies, and ecosystems as a whole.

States have negotiated the Compact domestically, and if Mexico is not at the table, they recognize that both the Upper and Lower Basins will have responsibilities to provide water in the event of a subsequent agreement; Years later the 1944 Treaty was ratified, but there was no clarity as to which basin was responsible for providing the water.. The fact that the states in 1922 saw fit to allocate Colorado water to the exclusion of Mexico speaks volumes about how their negotiators saw their neighbors to the south. Regardless, the 1944 Treaty guaranteed Mexico 1.5 million acre-feet of water annually except in the event of exceptional drought. While the Compact maintains that the two basins must share the obligation to deliver that water when there is not enough over and above US allocations, there is no agreement on what this means legally. For example, does the Upper Basin need to ensure that flows reaching the Lower Basin include an additional 0.75 million-acre-feet per year? What will this do to the Upper Basin’s chances of producing half of Colorado’s water?

The Compact was deliberately evasive incorporate appropriations for Native American Tribes, who remain virtually without decisions regarding the management of the Colorado River and in many cases have yet to gain access to their water. This seems extreme since the Supreme Court ruled based on the definition of Tribal water rights in 1908. Winters v. The United States believes that Tribes may have an implied right to water based on the terms of their reservation, with seniority based on the Treaty date of establishment of the reservation. Today, the 30 federally recognized Tribes in the Colorado River Basin have acquired rights to up to 20% of all Colorado River waters in the Basin. However, more than a third of the Basin Tribes have not yet settled their Colorado River water rights. Moreover, even those with settled rights still lack adequate infrastructure to access their water rights in a meaningful way, and all Tribes still lack a formal seat at the table where Colorado River management decisions are made.

The Compact does not recognize and does not recognize nature’s water needs. Nowhere in the Compact is there language that recognizes the value of water to natural systems as well as to the legions of birds, fish, and other wildlife that depend on freshwater-dependent ecosystems. That failure caps a century of devastating losses. Several programs have been established under the 1973 Endangered Species Act, but many of the Colorado Basin’s rivers remain unhealthy and at risk. Dozens of species of Colorado River fish and wildlife are listed as endangered or threatened, and the Colorado River Delta, a lush ecosystem of 1.5 million acres, was allowed to dry up and disappear in the middle of the 20th century. The US Bureau of Reclamation has raised the prospect that within the next year or two, it may be impossible for water to pass through Glen Canyon Dam, effectively removing the surface flows of the Colorado River from the Grand Canyon. The Compact’s promise of water for development depends on healthy rivers, and regional economies depend on sustaining natural systems. However, in its application, the Compact allowed harm to the Colorado River and its tributaries, to every living thing that depends on them, and to all of us who value it for recreational, cultural, and spiritual reasons.

The looming water crisis in the Colorado River Basin requires urgent management adjustments and adaptations to meet today’s challenges. As the Colorado River Basin States consider how they will share the dwindling water supply, they must simultaneously correct the errors, oversights, and shortcomings of the Compact. Audubon will continue to advocate for management that provides improved water reliability for the 40 million people who depend on it, increased benefits for Native American Tribes from their water rights, and sustainable habitat for hundreds of hundreds of species of birds and wildlife call it home. . The Colorado River Basin States must prove that this can be done through adaptation within the framework of the Colorado River Compact and the Law of the River. If they instead use the Compact and other venerable laws to argue that these results are not possible, they will prove that the legal framework will require more than adjustment—it will require complete reform.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.