[ad_1]

From the Summer 2022 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Over the past few months, one particular bird, believed to be an African Sacred Ibis, has garnered a lot of attention and spans many areas at Cornell University—from the College of Arts and Sciences to the College of Veterinary Medicine, the College of Engineering , and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Not bad for an animal that has been dead and mummified for over 1,500 years.

The so-called “mummy bird” had help on the tour. Carol Anne Barsody, a master’s student in archaeology, became involved in many different aspects of the research that took the bird to different places on campus as she tried to learn all she could about the artifact—part of Cornell University Anthropology Collections.

“One of the things I love about this project is that it brings together expertise from across Cornell, all working together toward a common goal,” Barsody said.

The exact origin of the mummy bird is difficult to determine. Since the late 1800s, mummies of all shapes and sizes and species have found their way to Cornell. Its physical appearance—a torn linen diaper, roughly the size of a football—reveals very little, and no record exists of the mummy’s arrival at the university, perhaps a century or more ago. . Since then, it has moved to various university collections, stored inside a box mislabeled “hawk mummy.”

Barsody himself found a unique route to the project. He first came to the university not as a student, but as an employee, with a background in mathematics, working for the Center for Technology Licensing. He then entered the university’s employee degree program and received full tuition to pursue a master’s degree in archaeology.

His main research interests are the ways technology can be integrated within museum exhibitions and how it can change museum collecting practices, access to collections, and aid in repatriation efforts. The mummy bird made for an effective case study. So Barsody set out to find collaborators who could use 21st-century technology to help him peer beneath the mummy’s wrappings without disturbing the artifact’s integrity.

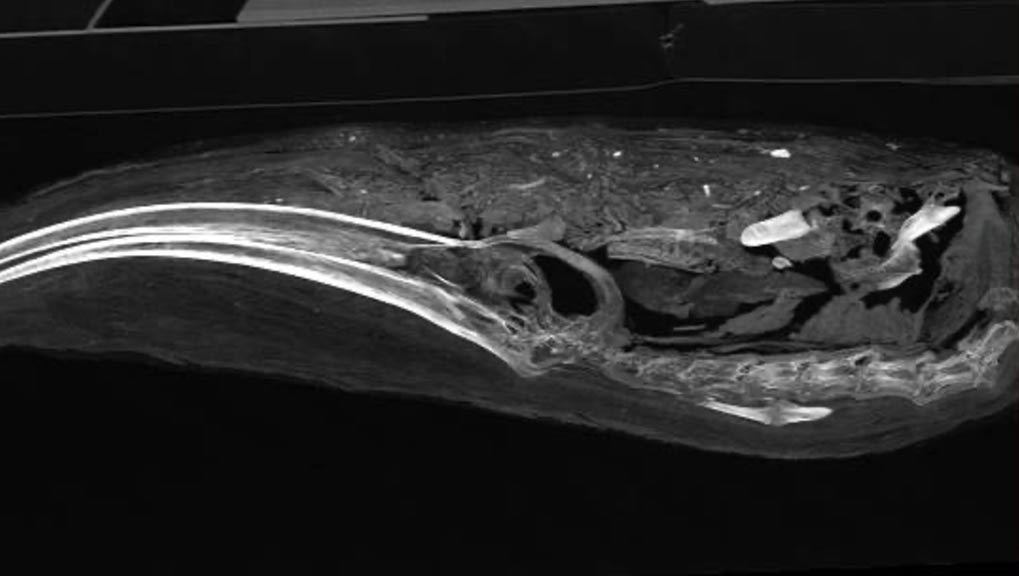

In November, Barsody and Frederic Gleach, curator of the Cornell Anthropology Collections, brought the mummy to the Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine, where an imaging technician performed radiographs and a CT scan confirming that their bundle did indeed contain a bird Not only that: The CT scan showed that some of the bird’s soft tissue and feathers were still intact.

Hoping to learn more about the biological and physiological characteristics of their bird, Barsody and Gleach brought the mummy to Vanya Rohwer, curator of the Cornell Museum of Vertebrates, located in the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

After reviewing the scans and consulting a database, Rohwer identified the bird as a male African Sacred Ibis, due to its general body shape and downward sloping bill. This isn’t a total surprise, Barsody says, since ibises are commonly mummified because of their association with death and Thoth, the god of wisdom and magic. Ibis are so popular, they are sometimes bred in large numbers for the sole purpose of being sold as votives. According to Birds of the World, 1.5 million ibis are buried in the catacombs at Saqqara, the site of a vast necropolis and pyramids in the ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis. Sacred ibises were common in Egypt until the early 19th century, but they almost completely disappeared by 1850 and are now extinct in the country.

Rohwer weighed the mummy, which came in at 942 grams, about the same as a liter of milk. As best they could tell, the bird was somewhere on the order of 1,500 to 2,000 years old.

“It’s fun to put these things together,” Rohwer said. “It’s a real-life puzzle.”

The most important piece of that puzzle may be the soft tissue revealed by the CT scan. Barsody now returned to the College of Veterinary Medicine, consulted with Dr. Eric Ledbetter, professor and head of the section of ophthalmology, about the prospect of obtaining genetic material through endoscopic microsurgery. If the bird’s DNA matches any other samples from a database of mummified sacred ibis, Barsody should be able to determine the temple where it was buried, and thus the age and the region in which it lived.

The next phase of Barsody’s project is more ambitious.

“I want to revive the bird,” he said.

Barsody is working with Cornell electrical and computer engineering undergraduate student Jack Defay to scan the mummy using open-source technology and smartphones to create a 3D model of the bird—an inexpensive method of artifact digitization. The mummy bird, its 3D model, and a hologram version will all be included in a multisensory exhibition Barsody plans to hold in Upson Hall on the Cornell campus in October.

“The goal is to gauge the public’s readiness for exhibitions without artifacts,” said Barsody, who currently works at Cornell’s Johnson Museum of Art. “That goes to larger questions about repatriation, institutional collecting practices, access, and education in this post-COVID world, where you might not actually be able to go to a museum.”

All the while, he continues to dig into university archives and historical records to learn all he can about the mummy and what it means to a culture that thinks so much of this bird, they kept it forever.

“It wasn’t just a living creature that people of the day might have enjoyed watching walk through the water. It was also, and it is, something sacred, something religious,” said Barsody. “Today, it has a lifetime of being studied, and respected, as a small representative of the amazing culture in which it is came from It has had many lives.

“I look at what I do as another way of extending its incredible life.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.